Hans NeurathThe Bial-Neurath FamilyThe Neuraths were members of a large Jewish community that was—with the exception of Warsaw— the largest in all of Europe. Vienna was by no means a Jewish city, as the anti-Semites maintained; yet the Jewish element was more visible and played a larger role in Vienna than in other western capitals. In 1867, Jews acquired equal civil, political, and religious rights with all other Austrian citizens. When Hans was born, there were roughly 170,000 Jews living in Vienna, making up about 9 percent of the population. This large community was composed of immigrants or their children who came from a wide range of linguistic, cultural, and religious backgrounds. They were rich and poor, urban and rural, traditional and already assimilated, German or Yiddish-speaking. Many looked for total assimilation; others wanted to preserve their Jewishness, whether defined by religious or ethnic criteria. Many Jews were very successful and quite a number had moved into the professions. Jews in 1909 made up 65 percent of Vienna’s lawyers, over half of its journalists and 59 percent of its physicians. Not by coincidence did Vienna experience an unprecedented cultural life with a high degree of Jewish participation and at the same time there arose a wave of anti-Semitism of previously unknown intensity. Anti-Semitism or the Jewish Question as it was called dictated political life, dominated the press, and conditioned everyday life to a greater degree in Austria and Vienna than in any other country or city. Arthur Schnitzler in his autobiography My Youth in Vienna wrote that it will hardly be possible for future generations to grasp the importance that was assigned to the so-called Jewish question. “It was not possible, especially not for a Jew in public life, to ignore the fact that he was a Jew; nobody else was doing so, not the Gentiles and even less the Jews.” During the First Republic, 1918-1933 There never was a time during the First Republic when antisemitism completely disappeared from the political landscape. It was strongest during times of political turmoil and economic hardship, i.e. the years following World War I (1919-1923) and the years following the Depression (1930-1933). Antisemitism was likely more intense in Austria than anywhere else in western and central Europe and not by coincidence Vienna during the First Republic was called the capital of anti-Semitism, reflecting the degree to which the disease had penetrated politics and society. Except for the Socialists, all political parties were anti-Semitic, the conservative Christian Socials as well as the nationalistic Greater German People’s Party and the fascist Austrian Nazis. Many private clubs—the notorious Alpenverein the prime example— and professional organizations had adopted antisemitic policies and excluded Jews from membership. Vienna’s anti-Semites demanded a numerus clausus, i.e. proportional representation, since Jews made up around 10% of the Viennese population they should only fill 10% of the positions in commerce, law, medicine, banking, newspaper publishing and editing and higher education. Naturally this ratio was only to be applied in fields in which Jews were overrepresented, not in fields such as civil service and school teaching where they were markedly underrepresented. In response to the frustrating political and societal situation and to escape from the problems they faced, Vienna’s Jews turned away from the public sphere to focus on the private, on family, career and personal life. Quite a number of childhood memoirs from this time tell of a happy family life, music lessons and music playing, soccer, family meals, and summer vacations in the mountains. And it was during the vacations while hiking with his family that Hans came to fall in love with the mountains, a love that was to define him lifelong. The fact that more and more vacations spas and hotels began to advertise that Jewish guests were not welcome must have contributed to the Neurath’s decision to take more of their vacations abroad. |

|

There were also positive developments. The antisemitic Christian Socialist Party, which had dominated Viennese politics since the 1890s, was replaced by the Socialist Party. With only one exception, the Socialists were to win absolute majorities in all municipal elections during the First Republic. Since the Liberal Party had disappeared almost completely, 75% of Viennese Jews—including the Neuraths—voted for the Socialists, in both municipal and national elections. And as a first sign of liberation on 21 December 1918, Dr. Neurath and his wife could finally attend a performance of Arthur Schnitzler’s play Professor Bernhardi—suppressed by the censor during the monarchy— at the Vienna Volkstheater. |

|

Looking for a new identity There was a serious identity crisis that characterized Austria during the First Republic and no doubt the identity crisis was most severe for Austrian Jews. The Neuraths like most Jews had been the most loyal Austrians, at the Monarchy’s end likely the only true Austrians left. In Austria-Hungary, not being a nation-state like Germany or France, Jews had been afforded the luxury of divided loyalties, of a three-fold identity: politically as Austrians, culturally as Germans, ethnically as Jews. Nobody required the Neuraths to adopt a non-existing Austrian national identity. This no longer worked as the collapse of the Monarchy changed everything. The New Republic proved not to be so tolerant and demanded the unity of political, national, cultural, and ethnic loyalty. The gentile German-Austrians did not develop a national identity of their own, to replace the old Habsburg one. They considered themselves ethnic Germans, i.e. members of the German nation, a reality Austrian Jews had a hard time adjusting to. “Jews regularly asserted their loyalty to the new Austrian Republic and their full participation in German culture, but they also insisted on a Jewish ethnic identity, not a German national one. As antisemitism grew and the Austro-German polity increasingly shunned Jewish participation, Jews responded by asserting their Jewish ethnic identity even more vigorously.” (Marsha Rozenblit) Hans in High School Jews made up an exceptionally high proportion of the student body in most Viennese Gymnasien; 30% of all Gymnasien students were Jews in a city in which only about 10% of the population was Jewish. This extraordinarily high percentage of Jewish students reflects Jewish success in acculturating but also the high value Jewish families attached to higher learning. Did Hans experience anti-Semitism in school and in his social life? It is difficult to imagine he did not. Antisemitism had penetrated everyday life of Viennese Jews, had become part of the cultural code, i.e. salonfähig and for that reason was not taken seriously. Compared to what Hans was to encounter later at the university, however, this was mild indeed. And there was safety in numbers: In many classes Jews made up the majority of students. |

|

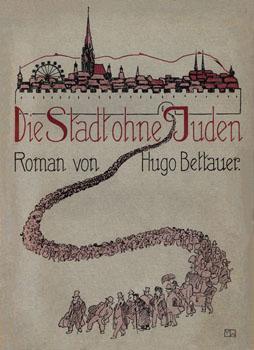

The case of Hugo Bettauer The case of Hugo Bettauer may serve as an illustration of the political climate at the time. Bettauer was the author of many popular novels and a highly controversial editor of progressive magazines. His satiric novel Die Stadt ohne Juden (The City without Jews) written and published in 1922 proved to be a strong response to antisemitism. In a Vienna of the future the city fathers decide to expel their Jewish citizens—with dire consequences for the economy, culture and social life of the city. The economy crumbles, theatres, libraries, and publishing houses stagnate or close. Cosmopolitan Vienna becomes a provincial town. Finally realizing that the city cannot do without its Jews, the Viennese beg the Jews to return. The novel became an immediate success and was made into a film in 1924. One year later, Hugo Bettauer was assassinated by Otto Rothstock, a member of the Austrian Nazi party. The murder trial became one of the most politicized events of the time. The jury obviously sympathetic to the defendant’s motives (“anti-Semitic rage”) declared Rothstock guilty but could not agree as to whether he was insane at the time of the murder. He spent two years in mental hospitals and was released in 1927. |

|

|

1927 This year - the year that Hans entered university - marks a break in Hans Neurath’s career but also in the history of Austria’s First Republic. 1927 is the year when public violence entered political discourse and when Austria was well on the road to civil war. The burning of the Palace of Justice in July provoked by the acquittal of those charged with shooting at a peaceful socialist demonstration, led to a bloody confrontation between the police aided by the right-wing Heimwehr militia and socialist protesters. This resulted in many casualties and in the growing belief that the Austrian Right might be on its way to crush the leftist opposition and create a Fascist Corporate State. The burning of the Justizpalast had nothing to do with Jews, yet the accompanying violence alarmed quite a number of them and it initiated the first wave of emigration from Vienna. While the writer Manes Sperber left, Elias Canetti, a fellow student of Hans at the chemistry department, considered it. |

|

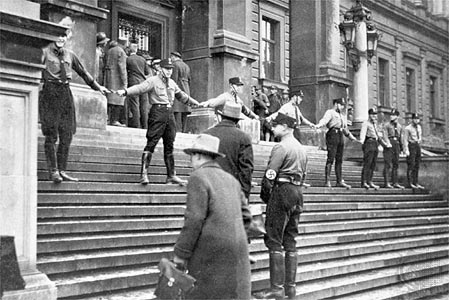

Burning of Palace of Justice Rally of the right-wing Heimwehr |

|

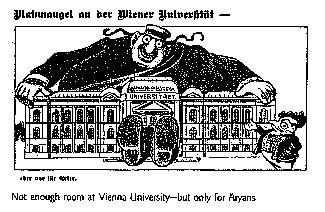

Radicals at the University of Vienna, Numerus clausus for Jews? When Hans Neurath became a student at the University of Vienna, he was confronted with a degree of violence he had not encountered before. By and large, Jews and gentiles had socialized well with each other during his time at the Gymnasium, in sharp contrast to what was happening at institutes of higher learning. Like Germany “no other group in Austria was so racially, passionately, and violently anti-Semitic as students of university age.” (Bruce Pauley) No doubt there was an economic competition for jobs between Jews and gentiles. Austria after the War had by far the highest percentage of students in all of Europe and a huge surplus of civil servants, which got even larger when as a result of the austerity program mandated by the League of Nations in 1922 thousands of civil servants were let go. The Viennese branch of the German Student Organization demanded enrollment restrictions for Jewish students and such were enacted at the Technical University and the College for International Trade but never at Vienna University proper. Right after the War, 46% of the students enrolled at the University of Vienna were Jewish, when Hans enrolled at the university that percentage had fallen to about 18%. Antisemitic demonstrations however continued.

|

|

Violence at the University There was much physical violence. Hans Neurath often witnessed organized beatings of Jewish students and at times the entrance to the University of Vienna was blocked by nationalist students in order to prevent Jewish students from entering. Lectures of Jewish professors were regularly disrupted; hordes of Austrian Nazis broke into classrooms and gave Jewish students three minutes to vacate the premises. Then they were attacked and beaten and thrown out of the building, often seriously injured. The tradition of academic autonomy—in force for centuries—permitted the most violent outrages against Jewish students to take place. The police stood by without interfering since they were prevented from entering the university and protecting the victims. Mostly sympathetic to the goals of the perpetrators, University officials rarely took action to restore order. Hans’ department was relatively remote from the main part of the university campus and escaped the unrest and terror initiated by the nationalistic student organizations. However, in February of 1931 Nazi students exhilarated by the great victory of their party in Germany in September last, broke into Hans’ home department, the Chemistry Institute, shouted anti-semitic slogans, sang the German national anthem and assaulted anyone who refused to stand up. The rioting continued for several days. |

|

|

Students are divided into Nations In February of 1930, the rectors of Vienna’s institutes of higher learning decided—under pressure from the German Student Organization— to divide the student body into four “nations”: German, non-German (Jewish), mixed and other. It was not up to the students to decide to which nation they belonged. Hans had to fill in four categories. The first three he was used to answer: Staatsbürgerschaft (citizenship), Heimatzuständigkeit (legal place of residence), and Religion with Austrian, Viennese, and Jewish. It was the new fourth category Volkszugehörigkeit (ethnicity), which was difficult to answer. “Austrian” was not acceptable; to be “German” he would have had to prove that his parents and all four grandparents had been baptized. “Jew” appeared to be the only possible answer. The regulation “was a thinly disguised plan to disenfranchise Jewish students in campus politics and in a broader sense to segregate them from the rest of Austrian society and turn them into second-class citizens.” (Bruce Pauley) The University loses its autonomy In June of 1931, the Austrian Supreme Court however ruled the regulations by the rectors’ conference to be unconstitutional. This in turn led to violent Nazi demonstrations and peaceful counter-demonstrations by Jewish students and protests by the Jewish Community Organization of Vienna to the Austrian government. When the anti-Semitic violence at the University continued and several American students were injured, the American legislation to Austria issued formal complaints to the Foreign Minister. Every year quite a number of American students—most of them Jewish medical students— came to Vienna still attracted by the reputation of the University’s Medical School but no doubt also swayed by the restrictive quotas against Jews at American colleges and medical schools. After some more American students were injured during the anti-Semitic riots, the American envoy met several times with the Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss as did envoys of other countries. By the end of 1932 violating the tradition of academic autonomy, police was allowed to enter institutions of higher learning in Austria as a result of which violence at the University of Vienna decreased. Hans NeurathThe Bial-Neurath Family |