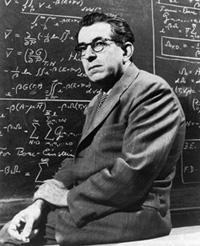

Hans Neurath

The Bial-Neurath Family

1938-1950: Professor of Biochemistry at Duke University

In 1938, Hans accepted a position as assistant professor in the Biochemistry Department at Duke University. Over the next twelve years he rose through the ranks to full professor of physical chemistry. He established a graduate program and a research program in physical chemistry of proteins, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and the National Institute of Health. Hans was first awarded an annual grant of $3,000 for three years, which was then increased and extended to $100,000 for seven years. This was the beginning of what would become 46 years of continuous support by the National Institute of Health.

950-1975: Founding Chair of Biochemistry at the University of Washington

Hans accepted the position at the University of Washington knowing full well that the task ahead of him would be daunting. The Medical School was new and the Department of Biochemistry was small, with only five faculty members, a dozen graduate students and two postdoctoral fellows. He was tasked with enlarging the faculty and space, establishing a graduate training program, and promoting the department’s growth in size, stature, and reputation. Over the years, this department grew into one of the leading biochemistry departments in the United States. In retrospect Hans said about his time in Seattle: “In many ways, the last 50 years at the University of Washington were the most exciting and rewarding years of my academic life. It was here that I could build up a long-range research program and derive the benefits of previous experiences in conducting basic research on proteins.”

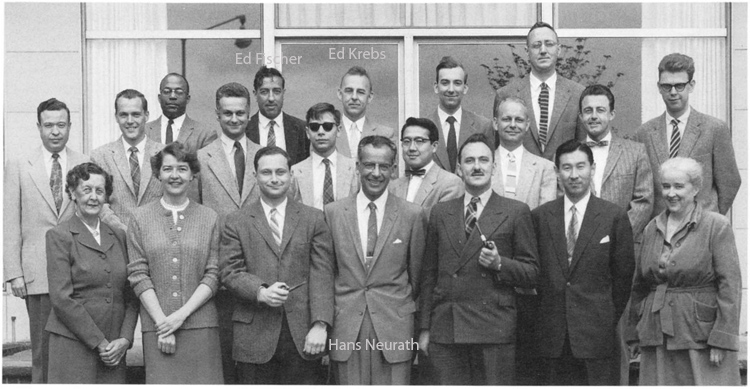

Hans Neurath with his research group in 1959

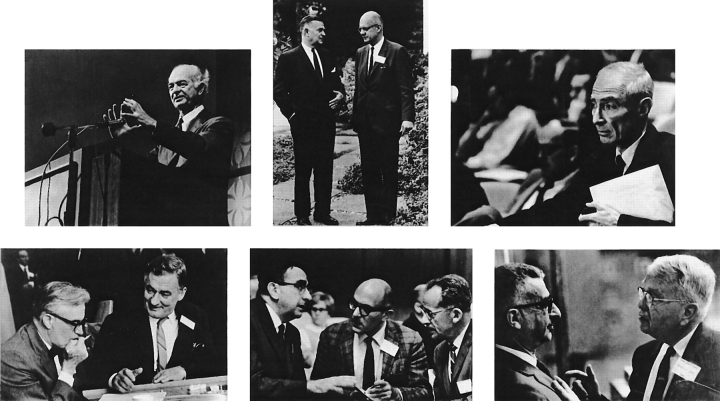

Whenever visitors passed through Seattle Hans asked for recommendations of promising young biochemists who might be interested in a faculty position. One of the most notable additions was Edmond Fischer, who, together with Edwin Krebs, would later earn the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Over the years, the department grew and expanded its program, so much so that they had to look for a new home. In 1965 a new building was completed to house Genetics and Biochemistry. The dedication of the new facilities coincided with a meeting of the National Academy of Sciences, which decided to meet at the UW, even though it had only two members among the University faculty (Hans being one of them). Nevertheless, seventy members attended, among them seven Nobel Laureates and also the well-known nuclear physicists Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller.

Meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in Seattle in 1965, marking the opening of the new Biochemistry–Genetics Building. Top row, left to right: Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling, President Charles Odegaard (University of Washington) with President Frederick Seitz (National Academy of Sciences); physicist Professor Robert Oppenheimer. Bottom row: biochemist Britton Chance and Nobel Laureate biochemist Hugo Theorell; physicist Edward Teller, University of Washington; physicist Boris Jacobson and biochemist Hans Neurath; biochemist David Rittenberg with Nobel Laureate Harold Urey.

|

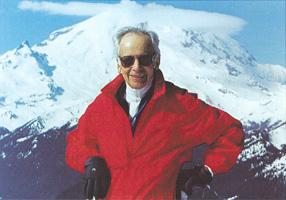

“When I came to Seattle it was essentially my first trip to the Northwest. I had no idea how beautiful it was.” Friends who knew Hans well suspected that considering his interest in mountains and mountaineering one reason he accepted the position at the University of Washington must have been Mount Rainier. However, people familiar with the Pacific Northwest are likely not surprised by Hans’ statement that he did not see the mountain until six months after he and his family moved to Seattle in September 1950. Mount Rainier, even if not the primary reason for coming to Seattle, remained a major attraction during the many years Hans lived in the Pacific Northwest. Although he never attempted to climb to the summit, he and his wife went hiking and skiing many times, whenever work allowed him to be away on weekends. Hans’ efforts surely contributed to keeping the park open all year. In March 1952 he wrote to the National Park Service: |

|

“As voluntary spokesman of a large group of residents who share the pleasures of skiing and mountaineering, I should like to submit to you herein the request of opening the highway to Paradise Lodge in Mt. Rainier National Park and of keeping this road open throughout the year.” Later Hans and his wife were able to acquire a cabin on forest service land, located within a few miles from one of the entrances to the National Park. They climbed on skis to Camp Muir at the 10,000-ft level dozens of times during winter and spring and enjoyed the 3,000 vertical ft. downhill run to the parking area. “My father was never happier than when hiking or skiing in the mountains,” his son Peter said.

|

|

| Hans in his eighties in front of Mt. Rainier |

Excursions

Reunion in Vienna. In 1972, there was a reunion in Vienna. On the occasion of the National Holiday on 26th of October the Austrian government organized an international conference on “The Future of Science and Technology in Austria.” Many national and international scientists were invited, some of whom-like Hans-were Americans of Austrian origin. For some it was their first visit to Austria in 35 years and so the conference had some appearance of reconciliation. The topic assigned to Hans was “The Future of Biomedicine,” which led him to discuss basic research in molecular biology, biophysics, and biochemistry, as well as drugs, food, and the technological use of enzymes. He concluded his discussion with: “I believe that the life sciences as a basic discipline as well as a technological enterprise provide vast opportunities for innovation and for economic development. The horizons of biology are expanding at an unprecedented rate and the developments of the biological sciences have profound influences on medicine and health care, on agriculture and other renewable resources.” He recommended a strong support of basic research by a partnership of the Federal and State Governments with private industry.

The social program included a performance of Mozart’s Magic Flute at the Vienna Staatsoper as well as a dinner dance in Schönbrunn castle, where he had a dance with Herta Firnberg, the Austrian minister for research, whom he had known when both were students at the University of Vienna and members of the same hiking club. On the last evening, Chancellor Bruno Kreisky invited all his former friends from the socialist fraternity to a Heurigen. For Hans it was “a strange sensation to be so intensely reminded of bygone days.”

Heidelberg. In 1975, Hans received the prestigious senior scientist award of the Alexander Humboldt Foundation and became thus a visiting professor in the Department of Zoology and was also appointed an honorary professor of the University of Heidelberg. He stayed for several months in Heidelberg, gave lectures on proteins and enzymes and established contact with the Max-Planck-Institute for Medical Research. While in Europe, he participated in scientific conferences in England, Switzerland, and Denmark. He accepted an invitation from the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences to visit research institutions in Moscow and Leningrad. Hans finished his year abroad at the University of Regensburg.

1975-1980: Scientific Director at Fred Hutchinson

In 1975, after twenty-five years as head of the department, Hans reached administrative retirement. He became scientific director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. This was a part-time position so he was able to continue his research program on proteins and proteolytic enzymes at the university. But he was successful in recruiting a number of outstanding scientists to the “Hutch.”

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

1980-1981: Scientific Director of the German Cancer Research Center

In 1979, at an international conference on proteins in Heidelberg, Hans was asked by a friend and member of the German Cancer Research Center whether he would be interested in assuming the position of scientific director of that institution, located in Heidelberg. The center was a large facility comprised of eight autonomous research institutes and 47 departments. Hans accepted the challenge, although friends and colleagues had warned him that the center was plagued by internal discord and strife. He signed a contract for three years, starting May 15, 1980. His appointment (“after tedious and complex negotiations”) was controversial because he did not belong to the inner clique of the center and was unwilling to compromise his standards of scientific quality and merit. “It became evident early on that any attempts to change the internal structure or the research goals, to introduce quality review, or to infringe on the self-interests of the institute directors would be vigorously opposed and all efforts to establish harmonious and constructive internal relations were sabotaged.” Hans asked a group of experts from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center to assess the quality of the DKFZ and to make recommendations. These experts in a report submitted after a 10-month investigation were “struck by the disparity between the fantastic physical plant, the enormous economical support given to the Center from the government, and the rather pedestrian research which goes on there (with a few remarkable exceptions).” “The Center—at present not a first-rate research institution—is in great need to become intellectually modernized.” Hans also felt that there were “some good scientists at the Center, but that the old guard of life-long Institutes Directors was a powerful minority group which resisted any changes that might affect their “Erbhöfe”.

The director of the institute of Nuclear Medicine, who was also Hans’ predecessor as scientific director, introduced neutron radiation for the treatment of cancer patients even though he knew that there was not enough evidence to justify this kind of therapy. Hans ordered that this procedure be discontinued for lack of evidence validating its effectiveness, whereupon the individual started a cabal of vicious accusations in the press against Hans’ leadership. This incident and the discord at the DKFZ were reported in all regional and national newspapers including FAZ, DIE ZEIT, DIE WELT and DER SPIEGEL, even on Bavarian TV and it became the subject of an inquiry by the Committee on Research of the German Parliament in a session to which Hans was invited as guest and witness. Following the inquiry, the person involved was forced to resign. But Hans decided that “enough was enough” and submitted his resignation effective December 31, 1981.

|

|

| Main administrative building at the German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg | Hans as scientific director of the DKFZ |

However, Hans was correct in feeling justified that his personal efforts and frustrations had not been in vain; the Federal Ministry for Research and Technology appointed an international committee of distinguished scientists that recommended a total overhaul of the center. The report was highly critical of the overall performance of the Center in basic research, for which two factors were largely considered responsible: the lack of effective external peer review and the lack of power that would allow the Center’s director to bring about changes. All in all, the report confirmed the need for the very changes and reforms that Hans had tried to implement. An interim director served at the Center until 1983, when Harald zur Hausen (who in 2008 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology) took over; during his tenure of twenty years he instituted fundamental changes in structure, authority, and programmatic planning. Today, the Cancer Research Center is a world-class scientific institution, with over 3,000 employees of which more than 1,000 are scientists.

Professor Emeritus

In 1979, as mentioned earlier, Hans had reached mandatory retirement and became professor emeritus. After returning from the Heidelberg adventure in January 1982, he continued his career as a scientist and teacher, even with somewhat reduced resources. In a letter to a colleague Hans wrote in 1985: “As to my current activities, I am fully occupied with research, some teaching and as editor-in-chief of Biochemistry. Out-of-town lectures, some consultation and related activities leave little time for hobbies, except hiking in the summer and downhill skiing in the winter which I take seriously.” The out-of-town lectures in 1984/85 were delivered in Houston, Texas, Caxombu, Brazil, Castello di Gargonza, Italy, Klosters and Zurich, Switzerland, Anaheim, California, Soedergarn and Stockholm, Sweden and Montreal, Canada. In the activity report for this academic year we read: “1. Recipient and principal investigator of an N.I.H. grant in the amount of $350,000 for three years. 2. Co-principal investigator with Dr. Walsh of an N.I.H. grant of $400,000 per year. UW receiving considerable overhead from these two grants. 3. Participates in two regularly scheduled graduate courses, i.e. Biochemistry 530 and 540, in addition to a weekly, regularly scheduled research seminar. 4. Serves on Departmental Committees as well as on Scientific Advisory Committee of the Dean’s Office, School of Medicine. 5. Supervises a post-doctoral research fellow and participates actively in research of joint research projects with Dr. Walsh. 6. Continues as editor-in-chief of Biochemistry. 7. Regular working hours daily from 8 to 5:30, Saturdays from 8:30 to noon.” Altogether hardly the schedule of a professor in retirement.

In September 1984, friends and colleagues celebrated Hans’ upcoming 75th birthday via a Symposium on ‘Modulators of Transformation Transfer’. Scholarly and social events took place at the Rosario Resort on Orcas Island. Hans must have been happy when among the many congratulations he found quite a number from his former colleagues at the Heidelberg Krebsforschungszentrum as well as clippings from German newspapers that paid tribute to his achievements at the head of the Center.

|

|

| At the Symposium on Orcas Island, 1984 |