Post-docs and fellowships in Vienna, London and the United States

Hans Neurath

The Bial-Neurath Family

1933: Vienna, Dissertation and Post-Doc

Although trained in physical chemistry and organic chemistry, Hans Neurath did his doctoral research in a small and relatively esoteric field of colloid chemistry (the term ‘colloid’ denoting a suspension of particles in a continuous medium). As his thesis advisor he chose Wolfgang Pauli, head of the Institute of Colloid Chemistry and father of the physicist Wolfgang Pauli who in 1945 was to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics. Hans completed his dissertation in 1933. He described his thesis as follows: “As a Ph.D. thesis I was assigned the project of preparing a highly purified, aqueous colloidal dispersion of ferric hydroxide and to determine the dependence of its stability and surface charge on electrolytes of increasing anion valence.” To continue his research he accepted a year as a post-doc volunteer in the Institute of Colloid Chemistry in Vienna.

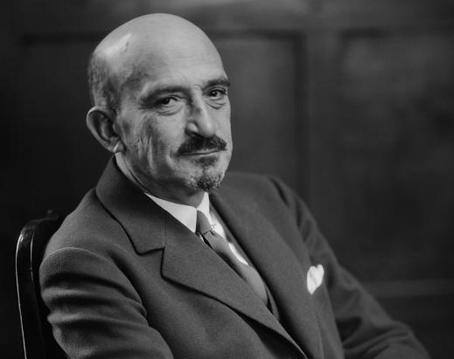

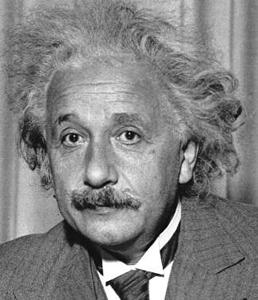

Prof. Wolfgang Pauli, Hans' thesis advisor Prof. Chaim Weizmann, First President of Israel, 1949-1952

1934/35: Post-doc in London

During the post-doc year in Vienna, Hans met some influential people, among them Professor Chaim Weizmann. Thanks to their recommendations he received a loan from the Academic Assistance Council, which enabled him to spend one year at Professor F.G. Donnan’s institute at the University of London. With N.K. Adams, he worked on the surface properties of proteins and fatty acids as models of biological membranes.

Career options in Germany and Austria

While in London, Hans had to consider his professional future? What were his chances of pursuing an academic career in Austria or Germany?

Political situation in Germany. In Germany the Nazis had seized power on January 30, 1933, less than two months later all opposition parties were outlawed and the following week the government sponsored a nationwide boycott of Jewish shops, a week thereafter a law “for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed which compulsorily retired Jews from the civil service and during the following months thousands of Jewish lawyers and doctors were being dismissed. The following month thousands of books by Jews and other “traitors and degenerates” were burned in German university towns. There was an exodus of hundreds of Jewish scientists, artists, journalists, and writers from Germany, all in all fifty thousand Jewish people left Germany in 1933, thirty thousand in 1934, twenty thousand in 1935. And after a lull in 1934, antisemitic agitation flared up in 1935 when the Nuremberg Laws codified a racial definition of Jews, turned them from citizens into “state subjects” and intensified their social segregation. A career for a Jewish scientist at a German university was clearly out of the question.

Political situation in Austria. There were similar developments in Austria but also strikingly different ones. In March 1933 chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss abolished parliamentary democracy and instituted an authoritarian Austrofascist state. In June the Austrian Nazi Party was outlawed as was the German Student Organization. The new constitution in 1934 explicitly guaranteed equal rights to all citizens including Jews. The government actively suppressed physical assaults on Jews, e.g. having the police protect Jewish students at the University of Vienna. Neither Dollfuss nor his successor Kurt Schuschnigg ever spoke publicly against Jewish Austrians. Among foreign pressures to fight against anti-Semitism and domestic pressures to support it, the government followed a middle-of-the-road position. There was discrimination of Jews in Austria but it was done in a quieter fashion not causing any headlines in foreign papers. In schools with a high percentage of Jewish pupils in Vienna, there were segregated classes established for Jewish and Christian students. Many Jews especially physicians lost their jobs. With very few exceptions in the Medical Faculty, even the most brilliant Jews were excluded from teaching careers by the simple expedient of unwritten faculty rule of denying Habilitationen to Jewish candidates. Even if Hilde and Hans did not have to fear physical assault while living in Vienna, the professional prospects of Hans in Austria would have been extremely slim. And considering the looming threat of a Nazi takeover of Austria by Germany, staying in Vienna was anything but safe.

Considering the academic job situation in Germany and Austria and the chilly political state in both countries, emigrating seemed a reasonable choice. “My friends and family couldn’t understand how I could leave beautiful Vienna and come to the wild United States. I was curious. Besides, I saw no professional opportunities in Vienna. And I didn’t trust the political situation.”

1935/36: Research fellowship in Minnesota

Through new contacts he was able to receive an offer from the University of Minnesota for a research fellowship for the coming year. About his year in Minnesota Hans wrote: “My life in Minnesota was simple and mostly goal-oriented. It so happened, that it was one of the coldest winters on record. I paid 15 cents for breakfast in a nearby drug store where the owner greeted me every morning with `Long live der Kaiser'.” Hans worked on the surface denaturation of proteins, especially egg albumin, which he had to prepare himself.

1936/38: Research fellowship at Cornell

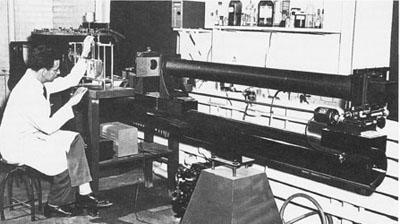

Baker Laboratory where Hans worked at Cornell. Hans, in 1936, working at Baker Lanoratory.