During her first quarter at the University of Washington, undergraduate Cheyenne Jobe spent time with a widow who habitually murdered her husbands. “Her troubled childhood landed her in a terrible place beyond her control,” Jobe explains. Classmates were equally understanding when they spent time with terrorists, serial killers, Nazis, drug lords, and other nefarious characters.

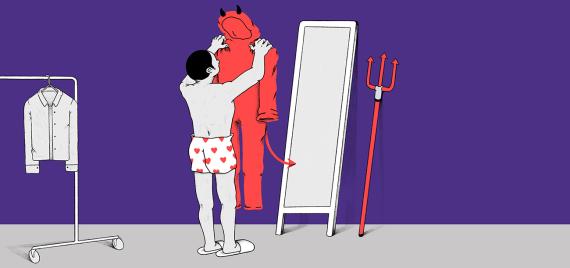

Fortunately none of the characters were real. They were villainous “types” that the students brought to life in Sympathy for the Devil, a 300-level Germanics course. The course explores how sympathy can be used for good but can also have a darker purpose.

Ellwood Wiggins, assistant professor of Germanics, created the course to dig into literature’s ability to elicit sympathy. “What drew me to literature in the first place was the belief that it can make us better by helping us identify with people from different backgrounds,” says Wiggins. “But the more I looked into it, the more problematic I realized that was. That’s the engine behind the course.”

Wiggins explains that sympathy is a term with several meanings. It can mean compassion for others and their suffering, but it can also mean empathy — feeling what another person feels. Both forms of sympathy are explored in the course, through philosophical treatises, speeches, plays, novels, and films. With each assigned reading, the class looks closely at the language used to persuade readers. In group assignments, the students then use those same techniques to elicit sympathy for less-than-sympathetic characters.

Ellwood Wiggins's students study the rhetoric and ethics of sympathy through philosophical treatises, speeches, plays, novels, and films. Photo credit: Matthew Leib/The Whole U

Writers have been doing the same for thousands of years. Compassion was an essential ingredient in Greek tragedy, which is where the course begins. Wiggins has students read The Persians by Aeschylus, first performed in 472 BC. The play, produced just twelve years after Persia invaded Greece, imagines how the Persians experienced the devastating news of their defeat. “The existential threat to Greek civilization was put on the stage and imagined from the perspective of the enemy,” says Wiggins. “Imagine soon after 9/11 having a blockbuster film from the point of view of al Qaeda.”

The remaining examples in the course, from a Shakespearean play to a Victorian novel to a 1930s German film, focus on depictions of Jews, a group that has been demonized as “other” through many centuries and societies. “Jews were the ‘bad guys’ in popular culture for so long,” says Wiggins, “so we look at artistic depictions that try to humanize them, creating admiration or sympathy for them. We look at how the dynamics of that works.” The course then flips that idea, ending with a contemporary Israeli film that features a sympathetic portrayal of a Palestinian terrorist.

Hopefully, after this experience, students don’t immediately pigeonhole people who come to opinions that they think are untenable.

Current events, including the recent attack on Jewish congregants inside a Pittsburgh synagogue, have reinforced the continuing relevance of the assigned texts. “The students have been reading Nathan the Wise this weekend,” Ellwood said right after the attack, referring to an 18th-century drama by German author Gotthold Ephraim Lessing about a generous and wise Jew. “I can't think of any better answer to hatred than Lessing's play about the need not for tolerance but for respect and friendship between Jews, Christians, and Muslims.”

Throughout the quarter, students work in small groups to analyze readings and use what they’ve learned to portray a demonized character sympathetically. Each group plucks a “bad-guy” character from a hat, ranging from a pimp to an abusive mother, and then brainstorms a name, backstory, and motivation for their character. Over the following ten weeks they prepare a speech, a dramatic scene, a first-person story, and a visual project to elicit sympathy for their character.

Working in small groups, students discuss how to create sympathy for the "bad guy" they have been assigned. Media credit: Corinne Thrash

Along the way, ethical questions abound. The class reads Aristotle, for whom compassion is an emotion involving cognitive judgments. They learn that compassion is manipulative and can persuade us of bad things as easily as good. The students also read Adam Smith, who describes all behavior through sympathy, with people acting and reacting to maximize the sympathy they receive. For junior Khoi Nil, who took the course during his freshman year, those reading assignments were his first exposure to philosophy. “I only realized later that this class was my first contact with ethics,” says Nil, now a philosophy major.

Sympathy might sometimes be morally wrong, but the students nevertheless try to inject humanity into their assigned characters. They present their first project — a five-minute speech — to the class, with their classmates playing the role of jurors at a sentencing hearing for the character. “The students who give the speech really ham it up, using humor and sob stories to try to get their fellow students to feel sympathy,” says Wiggins. Based on the speech, the classmates vote on whether there should be leniency in the character’s sentencing.

To argue for the black widow who kills her spouse, Jobe’s group gave the widow valiant motives and blurred the lines between right and wrong. Jobe, now a junior majoring in landscape architecture and comparative history of ideas, says the class has made her more discerning when she reads the news. “I definitely have a more critical lens and a better understanding of the ways that sympathy and empathy can be used to manipulate people,” she says. “But I also think empathy is extremely important for making more ethical, equitable systems. It’s a constant battle. You have to monitor yourself.”

Wiggins agrees. Since the contentious 2016 election, he has added a mini-assignment in which students take on the role of various political types — die-hard Trump supporters, liberal feminists, non-voters — and write flash fiction to present their character in a sympathetic light. This, he says, may be the most important assignment of all.

“In our society, on both sides of the political spectrum, we tend to see each other as these unsympathetic demons,” says Wiggins. “There’s this inability to put yourself in the other side’s shoes. Hopefully, after this experience, students don’t immediately pigeonhole people who come to opinions that they think are untenable. The more we practice doing this, the better.”

Sympathy for the Devil, offered by the Department of Germanics, is cross-listed with Philosophy and Comparative Literature. For more information, visit the Sympathy for the Devil website.

Here is the link to the entire A&S Perspectives article on Ellwood’s course: https://artsci.washington.edu/news/2018-11/trouble-sympathy#